Experimental error is an essential concept in scientific measurements, closely related to accuracy and precision. Understanding these terms is crucial for evaluating the reliability of experimental results. Accuracy refers to how close a measured value is to the true or accepted value, while precision indicates how consistently measurements can be repeated. Errors in experiments can be categorized into two main types: random errors and systematic errors.

Random errors arise from unpredictable fluctuations in measurements, leading to results that can be either too high or too low. These errors are often due to uncontrollable factors and can be minimized by taking multiple measurements and averaging them. For instance, if a measurement fluctuates between being 1 gram too heavy and 2 grams too light, this variability exemplifies random error. The averaging process helps to reduce the impact of these random fluctuations, enhancing the reliability of the results.

In contrast, systematic errors are consistent and predictable, resulting in measurements that are consistently too high or too low. For example, if a scale consistently reads 1 gram too heavy, every measurement taken will reflect this bias. Systematic errors can be more challenging to detect because repeated measurements may yield the same erroneous value, leading one to mistakenly believe the results are accurate. Identifying and correcting systematic errors is crucial for improving measurement accuracy.

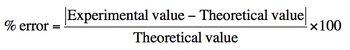

To quantify the accuracy of measurements, the percent error formula is employed. Percent error is calculated using the formula:

\[\text{Percent Error} = \left( \frac{|\text{Experimental Value} - \text{Theoretical Value}|}{\text{Theoretical Value}} \right) \times 100\]

In this formula, the experimental value is the result obtained from the experiment, while the theoretical value is the expected or accepted value from literature. A percent error of less than 10% is generally considered acceptable, indicating that the measurements are reasonably accurate. For example, if the theoretical weight of an object is 25 grams and the experimental measurement is 24.8 grams, the percent error would be calculated to assess the precision of the measurement.

Understanding these concepts of experimental error, accuracy, and precision is vital for conducting reliable scientific experiments and interpreting data effectively. By recognizing the types of errors and applying the percent error formula, students can enhance their experimental techniques and improve the validity of their findings.