Welding

Equip future welders with skills for success

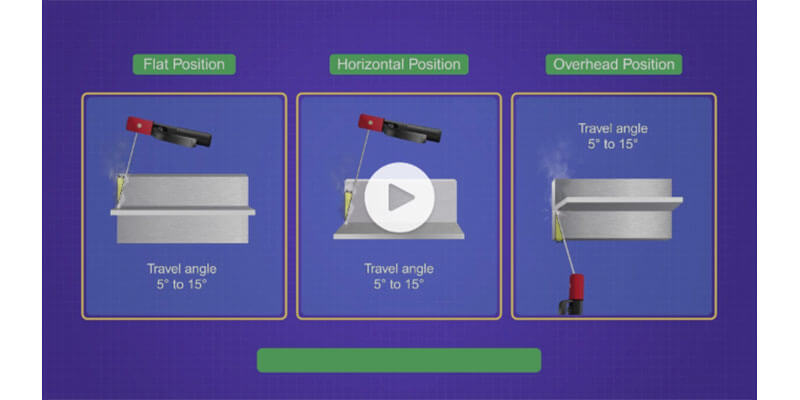

Videos

Support visual learners. Watching skills in action helps students build competence and confidence.

Animations

Improve comprehension. Lively visuals deepen students’ grasp of automotive skills and concepts.

Video uploads

Put learning into practice. Students can upload videos of themselves performing skills.