Setting the national picture for pupils with social, emotional and mental health needs (SEMH)

Malcolm Reeve, Executive Director for SEND & Inclusion at Academies Enterprise Trust (AET), highlights key statistics and indicators of the national picture for pupils with social, emotional and mental health needs (SEMH).

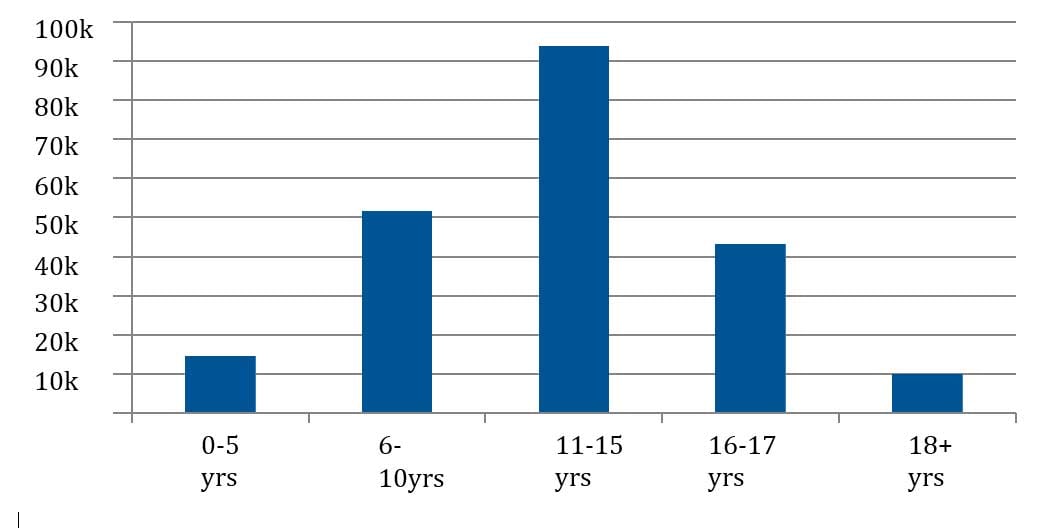

The issue of pupil mental health has become much more prominent in recent months and is also now one of the four broad areas of special educational need. This is only right in light of the fact that three quarters of mental health problems start before the early 20s[1] and referrals to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services are most common in the age range 11-15 where there were over 90k referrals in 2015[2].

Our understanding and focus upon children’s mental health has been enhanced by the changes brought in by the revised SEND Code of Practice in 2014 in which the old category of ‘Behavioural, Emotional and Social Difficulties’ (BESD) was replaced by a new one ‘Social, Emotional and Mental Health’ (SEMH) needs.

Of the four areas of special educational need SEMH is the one, which is in a sense, most challenging for schools. There is a wealth of readily available resources for the other areas and lots of expertise exists in the system already. However, for SEMH the expertise and resources are less prevalent and the joining up of mental health services with schools is less developed.

The Children’s Commissioner’s Lightning Review (May 2016) found that 1 in 250 children were referred to CAMHS. Worryingly 28% (67,200 children) were not allocated a service and one CAMHS reported that 78% of referrals were turned away. There is a great variation in CAMHS across the country.

The National Picture

It’s not straightforward to fully understand the national picture except to say that much more needs to be done. We do know that there were 240,000 referrals to CAMHS services for children in 2015 and we know their ages:

We know the national figures on those with special educational needs within the category SEMH. These figures demonstrate that numbers of children with SEMH in special and secondary schools are remaining fairly constant but there was a big increase in numbers in primary schools between 2015-16. The actual numbers are:

| SEN/SEMH in Schools in England[3] | Primary | Secondary | Special |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 83,595 | 72,065 | 13,450 |

| 2016 | 96,180 | 72,257 | 13,493 |

This correlates with what I was finding ‘on the ground’ in my travels in the past year: an increasing number of primary schools telling me they were being challenged by larger numbers of children with social and emotional needs.

There is one health warning on the Department for Education (DfE) figures above for schools. These are the numbers for children who are designated as having a ‘special educational need’ in the primary category of SEMH.

Many children will have a social, emotional and/or mental health need who do not have a special educational need but we do not have the numbers for these children. So we know the issue is bigger than these figures tell us but we don’t know how much bigger.

What can schools do?

Schools can proactively tackle the following:

- Accept as a starting point that SEMH both for children and staff is a key aspect of their work and commit to developing their expertise and deploying their resources accordingly. You could appoint a mental health lead; this happened as part of a pilot project across 200 schools in England this year and I am hearing very positive things about the benefits.

- Fully understand that group of children in the school who are designated with a special educational need in the broad area of SEMH. We know that on average in English schools in 2016 this group represents 15.5% in primary, 18.5% in secondary and 12.6% in special. So the question is how does your school compare?

- Add to this group any child the school considers as having a SEMH need but not a special educational need including of course all referrals to CAMHS.

- Now that we have a true picture of the school’s SEMH population there are two questions which must be asked and answered: What is the service? Where is the expertise?

In answering these two questions the DfE’s very helpful updated guidance on mental health and behaviour[4] should be useful. It contains nine key points and key references for good practice and resources.

As I have said, this area is one of the most challenging for schools but I hope these pointers may help in some way. In the schools I work with we will be further stepping up our response to these challenges in 2016-17 and hoping to make a bigger difference.

References

[1[ Kessler R et al (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 62, 593-602

[2] Lightning Review: Access to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services, May 2016

[3] DfE: Schools, pupils and their characteristics (January 2016)

[4] DfE: Mental health and behaviour in schools: departmental advice (March 2016)