World-Class Digital Learning in Action at EELU: A Strategic Partnership with Pearson

Discover what a successful digital transformation partnership looks like in practice at the Egyptian E-Learning University (EELU).

Discover what a successful digital transformation partnership looks like in practice at the Egyptian E-Learning University (EELU).

Discover how Professor Gerard Nagle’s use of Mastering Engineering transformed student engagement and boosted performance in Fluid Mechanics.

Of all the courses on a business student’s schedule, which one is most likely to be met with a sense of dread? For many, the answer is statistics. It’s a challenge every educator in the field recognizes: students entering the classroom already armed with anxiety, anticipating a semester of dense, abstract concepts. This anxiety, as author and educator Dr. Serina Haddad notes, often “turns into a cycle of self-doubt and affects their performance.”

So, how do we as educators break this cycle? How do we transform the statistics classroom from a place of fear into a hub of curiosity and empowerment? Drawing on her years of experience in the corporate world and over 14 years of teaching statistics at Rollins College and other higher education institutions, Dr. Haddad believes the answer lies in forging a powerful connection with students by making data immediate, relevant, and interactive.

Dr. Haddad’s approach begins with a simple premise: demystify the subject. “We really need to show the relevance,” she insists. “We need to show how simple the content is and how it connects with day-to-day things that they go through.” Instead of diving into complex theory, she starts with accessible examples, like calculating the average time it takes to get to class. This small shift reframes statistics not as an obstacle, but as a tool for understanding the world.

Technology, when used thoughtfully, becomes another key ally in reducing anxiety. Dr. Haddad has found that breaking down MyLab assignments into smaller, more manageable chunks keeps students engaged and builds their confidence. But the real game-changer in her classroom is Excel.

“For me, Excel is a foundational tool for classroom instruction,” she explains. Far from being just a program for basic formulas, she uses it to facilitate interactive learning. “It allows students to work hands-on on a data set during class and see results immediately, and that helps them feel included.” By using a tool that is inexpensive, widely used in business, and central to their internships and future jobs, students see the immediate value of their learning. This hands-on approach, where students can manipulate data and see the story unfold, sparks genuine interest and keeps them invested. Recognizing this, the fourth edition of her textbook, Business Statistics, now includes customizable Excel files for each chapter, allowing instructors to seamlessly integrate this active learning model into their own courses.

Beyond the classroom, the entire landscape of data analysis is shifting, and Dr. Haddad argues that our teaching must evolve with it. “There is a clear shift from computation to actual interpretation,” she states. With software handling the heavy lifting of calculations, the crucial skills for today’s students are interpretation and storytelling. The essential question is no longer just “What is the answer?” but “What are the numbers telling us?”

This shift underscores the growing importance of data literacy. Dr. Haddad captures her students’ attention with a powerful statistic: one in five U.S. students earns a business degree. “What is your competitive advantage?” she asks them. The answer, she posits, is data proficiency. To compete, students must be able to not only analyze data but also think critically and derive meaningful insights—a skill developed through experiential learning. By having students download and experiment with real-world data sets through MyLab Statistics, they learn to see beyond the numbers, make mistakes, and build the problem-solving skills essential for their careers.

Keeping up with technology, particularly the rapid developments in AI, is another challenge educators face. Dr. Haddad encourages a mindset of lifelong learning, advocating for embedding AI tools into the curriculum. This includes the critical conversations around ethics, bias, and the danger of over-reliance on these powerful new tools. “I think Pearson is doing a fantastic job keeping up with technology and building AI tools to help

instructors and students. Students are able to practice with a customizable study plan, seeing their strengths and weaknesses when they work with problems,” she states, “it’s an amazing way to use AI for learning.”

Dr. Haddad’s vision is a powerful reminder that teaching business statistics is about more than formulas and distributions. It’s about empowering students to become confident, data-literate professionals who can cut through the noise, tell compelling stories with data, and hold a competitive edge in a world that demands it.

Her approach transforms the classroom into a dynamic space where anxiety is replaced by engagement, and abstract theories are made tangible. The new “Focus on Analytics” feature in the fourth edition of Business Statistics further bridges this gap, showing students the direct, real-world application of statistics in business analytics.

Picture this: You're standing in front of a classroom full of biology majors who need to understand physics, but their eyes glaze over the moment you mention velocity or force equations. They're scrolling through their phones, probably Googling "physics shortcuts" or watching questionable YouTube videos that oversimplify complex concepts. Sound familiar?

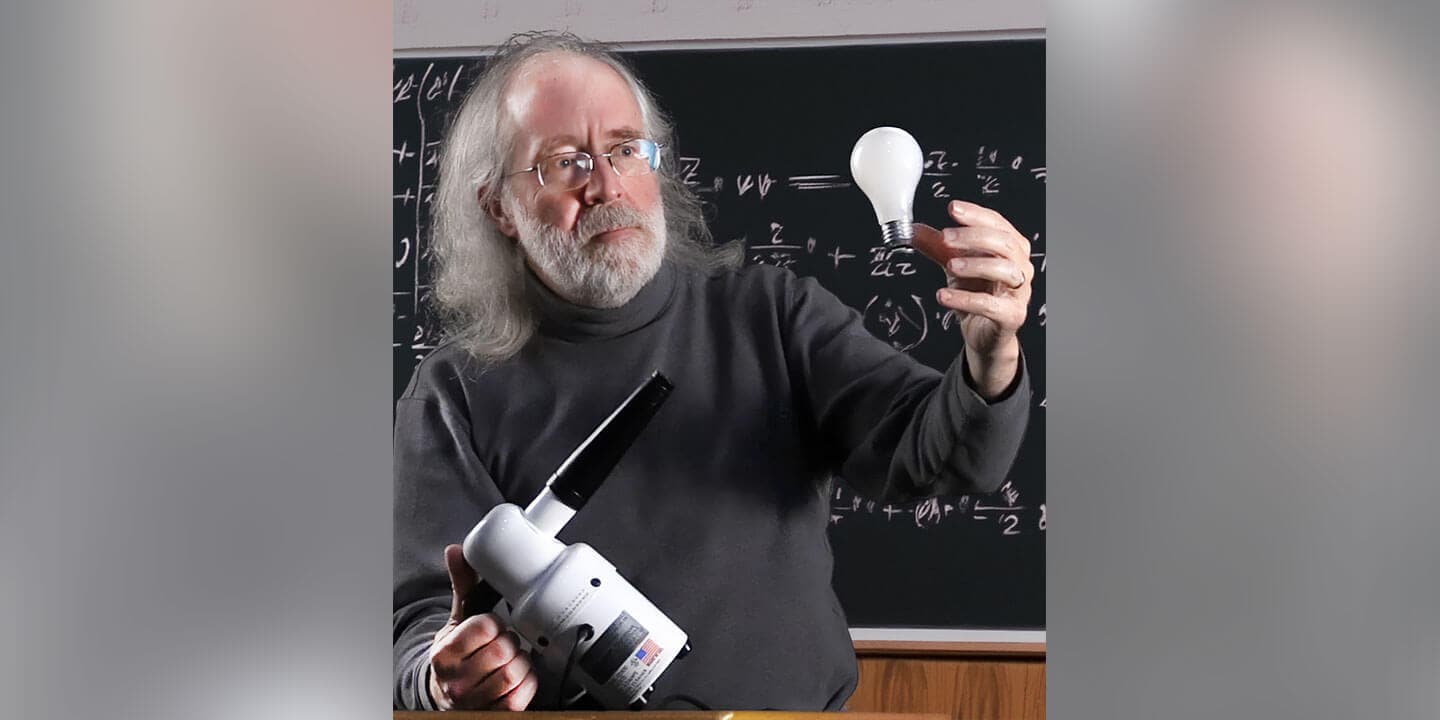

This all-too-common classroom challenge is what drove Brian Jones, a physics educator with over 40 years of experience, to revolutionize how we teach physics to life science students. His journey from classroom frustration to textbook innovation offers a roadmap for educators grappling with similar challenges in our increasingly digital world.

Jones discovered early in his career that traditional physics education wasn't connecting with his students. "They aren't going to be physicists," he realized. "They're going to be in other fields, mostly the life sciences." This revelation became the cornerstone of his educational philosophy and the driving force behind his work as a co-author on College Physics: A Strategic Approach and University Physics for the Life Sciences.

The transformation wasn't immediate or easy. "When I first started teaching a college physics course and I realized I need to have examples from the living world to engage my biology students, that meant I had to go and learn a whole bunch of biology," Jones admits. "It was intimidating, and my students know a lot more about it than I did, so that was hard."

But this vulnerability became his strength. Instead of retreating to abstract physics problems, Jones embraced the challenge of making physics relevant to future healthcare professionals. The result? A curriculum filled with problems about jumping whales, blood flow dynamics, and neural conduction—real-world applications that suddenly made physics not just understandable, but essential.

"The students love that," Jones observes. "They're motivated to read the book because they understand the problems are realistic, the situations are realistic, and it's teaching them not just about physics, but why physics is important to their lives and careers."

Jones's approach goes beyond simply changing problem sets. His work represents a fundamental shift in how we think about disciplinary boundaries and educational resources. "We have a real strong emphasis on pedagogy, understanding how students think about the world and helping them understand how we talk about the world in physics," he explains.

This pedagogical foundation supports what Jones calls an "ecosystem" of learning resources built in Mastering Physics and the Pearson eTextbook. Rather than treating digital tools as add-ons to traditional textbooks, his team has created an integrated approach where every component—from pre-lecture videos to interactive tutorials—works together seamlessly.

"They're a cohesive whole. They all use the same terminology. They all use the same concepts. They're consistent. They're coherent," Jones emphasizes. This coherence addresses a critical challenge many educators face: how to maintain quality and consistency across multiple learning platforms.

The innovation extends to addressing modern classroom realities. Jones tackles head-on the question that many instructors ask themselves: "How do I keep my students from just going out and Googling things, or finding a video on YouTube that is of dubious quality?" His solution isn't to fight technology but to provide better alternatives—curated, accurate, and pedagogically sound resources within Mastering Physics that students actually want to use.

For instructors worried about venturing into unfamiliar territory, Jones offers reassurance: "You can trust that anything you find in the book is real and is realistic. You don't have to learn any biology. We've done the homework for you."

At the heart of Jones's work lies a deeply personal mission. "I define myself as a physics educator," he states. "I came to writing a textbook because I was frustrated about the quality of resources that were available and so I have made it my life's mission to create a book which will help support instructors."

This isn't just professional dedication—it's recognition of the profound impact educators have on their students' futures. His message to fellow instructors is both humble and empowering: "You know how your students learn. You know what they need, and we're just trying to provide you with the tools that you need to better do your job."

Perhaps most inspiring is Jones's commitment to continuous improvement. "Our next editions of these textbooks are still in production. The authors are still living and breathing and educating. We're still making stuff," he says. "The new versions of Mastering Physics and the eTextbook are allowing us to really dream big."

Brian Jones’s story is a powerful reminder that the frustrations we experience in the classroom can be the very seeds of innovation. His work offers a compelling model for how to build bridges between disciplines, engage students with real-world relevance, and create a supportive, high-quality learning environment.

Meet Eric Simon—Harvard-trained biologist, passionate educator, and humanitarian who proves that great teaching extends far beyond the classroom walls.

Eric Simon's journey to becoming one of biology education's most innovative voices began with an unusual combination: computer science and biology. "When I was an undergraduate, I really enjoyed both computer science and biology, so I actually became a double major," he explains. This unique background in computational biology would later prove invaluable as he became a pioneer in educational technology.

After earning his PhD in biochemistry from Harvard, Eric discovered his true calling wasn't just in research—it was in teaching. "While I was at Harvard, I worked as a teaching fellow and found that I really enjoyed teaching. I actually became a teaching consultant in their Teaching and Learning Center and knew by the time I graduated, I wanted a job that had a pretty strong teaching emphasis."

That was over 25 years ago, and Eric has never looked back.

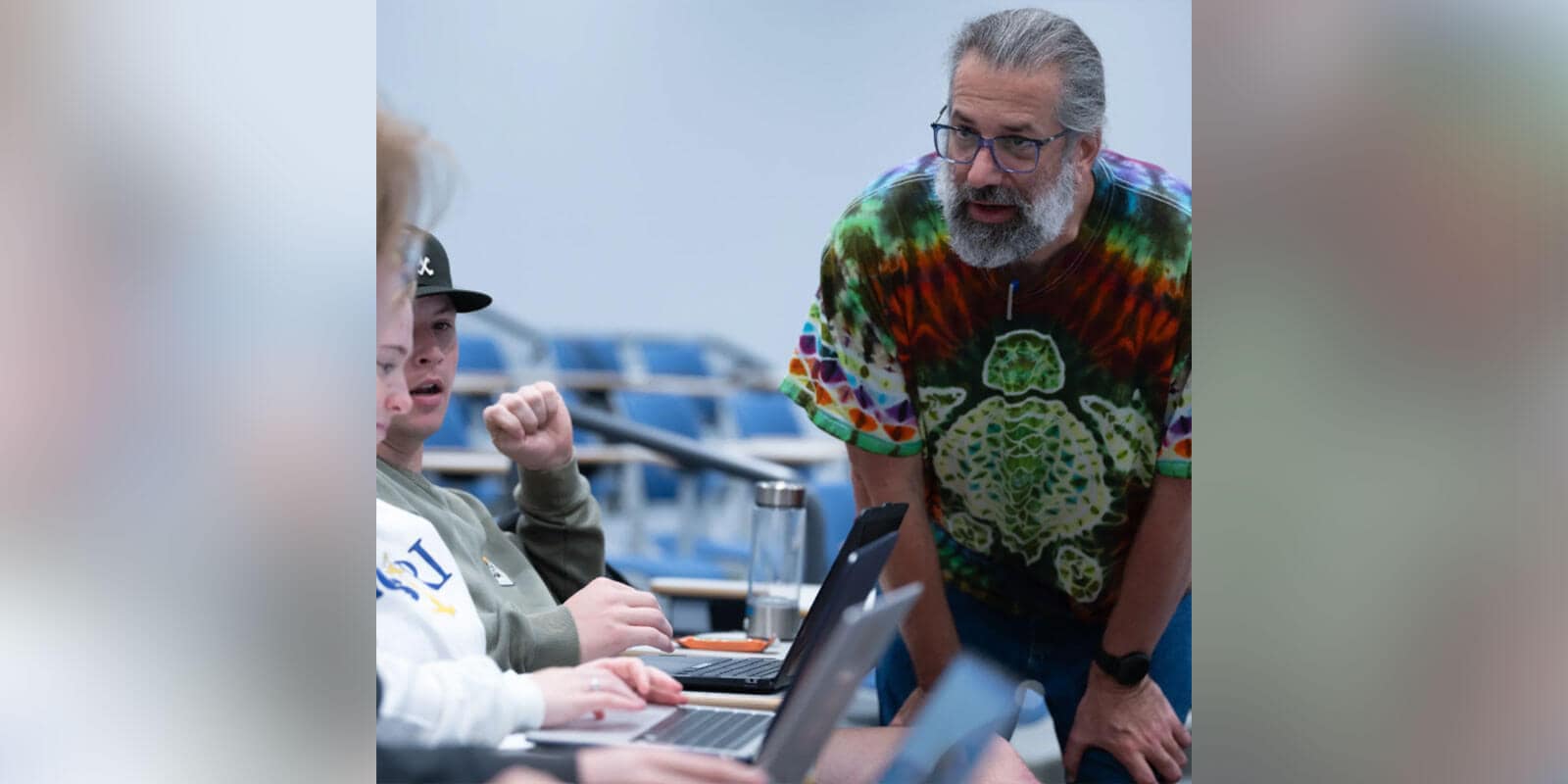

What sets Eric apart is his specialization in something many educators find challenging: teaching non-science majors. "I found that what I actually like the most is teaching non science majors. I've been specializing in teaching non majors introductory biology courses for the last 23 years at New England College. It's just a really, really satisfying job for me, and I really enjoy trying to explain science to non-scientists."

His secret? Understanding that biology isn't abstract—it's everywhere. "Biology is all around us. Everybody knows the importance of biology in their lives. I always tell my students you don't have a choice about whether or not this topic will affect your life, because it will. Your only choice is whether you approach it from an educated standpoint or not."

Eric also taps into what renowned biologist E.O. Wilson called "biophilia"—the innate love humans have for nature. "Almost everybody when they see a turtle, they go, 'oh,' and they're attracted to it. So I try to tap into that inner biophilia that I know exists in all my students."

Eric has completely transformed his approach to education over the years. "In the last several years I've moved pretty far away from any kind of lecturing. Now most of our time, about 3/4 of our time in the classroom is spent on small group activities where the students are helping each other."

But his innovation goes deeper than collaborative learning. Eric focuses on equipping students with life skills, not just biological facts. "My favorite type of assignment is one that is providing them with a skill that they will be able to use later in their lives. If I'm helping you learn how to take a large body of information and summarize it in a way that you can then quickly get the answers you need, that's going to be a skill that's going to help in whatever job you have."

Eric's path to authoring began with his forward-thinking approach to technology. "Around 1999, I was a very early adopter of instructional technologies. I was creating websites for my courses before my school even had a website." This innovation caught the attention of publishers, leading to his integration into the Campbell author team and eventually to his work on Campbell Essential Biology.

His favorite innovation? The "Teach Me, Show Me, Quiz Me" feature that transforms static textbook figures into dynamic learning experiences. "Instead of seeing the finished figure, you get a video of me explaining the figure and building it up piece by piece. Then students can view the complete figure, and finally, they have to build the figure themselves by putting labels in the right places."

Perhaps Eric's most important contribution is preparing students to navigate our information-saturated world. "Probably the single most important skill that I'm trying to teach my students is how to recognize reliable scientific information. Students have the world at their fingertips, and they have to learn to be their own librarians."

He continues: "If I had to pick one thing that I want them to learn, it's not some piece of content, but rather it's the skill of how to distinguish reliable scientific information from bogus scientific information."

Beyond his classroom innovations, Eric demonstrates extraordinary compassion through his humanitarian work in Tanzania. What started as a simple mistake—bringing thumb drives to a school without electricity—became a life-changing mission. "I met the head of the school and asked what they needed. She said, 'We need food. These kids walk up to 5 kilometers, spend 10 hours in school, then walk home 5 kilometers without any food.'"

Today, Eric's charity feeds 1,400 students across two schools every day of the school year. "We’ve been able to bring the price of lunch way down by buying in bulk, in advance, from local farmers," he explains, describing how he personally travels to Tanzania each July to support this cause.

The impact has been transformative: "Because we started feeding the kids, enrollment went up from 850 to 1,315. Retention went up, test scores went up." The community even named their second school after Lucas Mhina, Eric's local partner who helps coordinate the food delivery.

Eric's commitment to education extends beyond traditional boundaries. He leads international trips for both students and lifelong learners, taking groups to places like Machu Picchu, Tanzania, Costa Rica, and Panama. These experiences enrich his teaching and provide real-world contexts for biological concepts.

His current focus on teaching "relevant skills" rather than just relevant content represents the cutting edge of educational thinking. "Pretty much everybody does relevant content now. What most people don't think about is how to teach relevant skills—skills that cut across all content areas and beyond biology."

Eric Simon embodies what it means to be an educator in the fullest sense. From his innovative textbook features that help students visualize complex processes, to his

humanitarian work that literally feeds hungry children, he demonstrates that great teaching is about more than transferring knowledge—it's about transforming lives.

In a world where scientific literacy has never been more crucial, educators like Eric are ensuring that every student—whether they become scientists or not—leaves the classroom better equipped to understand, evaluate, and engage with the world around them.

Eric Simon proves that the best teachers don't just educate minds—they touch hearts and change the world, one student at a time.

If you would like to learn more and connect with Eric Simon directly, please reach out to him at SimonBiology@gmail.com

At the University of Tampa, math students must master challenging concepts to succeed in their coursework; however, this is most often easier said than done. Students must first grasp key math fundamentals before advancing to more demanding concepts. What’s more, instructors must have the tools to identify whether students understand prerequisite content and whether they’re absorbing new material as it’s presented.

MyLab® Math from Pearson, which combines respected content with personalized engagement to help students and faculty see real results, is empowering a University of Tampa math instructor to keep his finger firmly on the pulse of his students’ mastery. The learning platform helps him make real-time adjustments to his instruction and avoid teeing up more complex concepts before his students are proficient in material he’s already delivered.

Prof. Sasko Ivanov, a lecturer in mathematics at the 11,000-student private institution located in downtown Tampa, Florida, has been a loyal Pearson user since before joining the school in 2010. He’s made MyLab Math a staple in the main three courses he currently teaches: College Algebra, Precalculus, and Calculus for Business.

“I'm really grateful and thankful to Pearson for creating MyLab,” he says. “I find it really helpful, and I get very positive feedback from my students about how helpful it is.”

Many University of Tampa students must complete College Algebra as part of their general graduation requirements. Some students, such as nursing and pre-med majors, must take Precalculus before moving on to Calculus. Business students must take Calculus for Business.

“As part of my strategy at the beginning of each semester, I don’t assume that everyone is coming from the same knowledge background,” says Ivanov. “I review a lot of topics from College Algebra. In Calculus for Business, you’re expected to know everything about adding and subtracting fractions. In my experience, I find that’s not the case. Most students struggle with basic concepts.”

For example, Ivanov reports that more than two-thirds of students struggle with factoring — the process of finding what to multiply together to get an expression. Proficiency in the skill is essential in Calculus for Business. So Sasko takes a step back to assess where the learning gaps are and how he will try to fill them.

Learning Catalytics, a standout feature within the MyLab Math suite, helps Ivanov identify and target key gaps. In fact, he’s integrated it into his daily class cadence.

“I love Learning Catalytics; I was so happy when I discovered it,” says Ivanov. “I get real-time feedback about what students have learned in the previous class and whether they’re prepared for the section we’re about to cover.”

The interactive student response tool allows him to rapidly deploy questions and surveys while assessing student comprehension. He uses the real-time data to fine-tune his instructional strategy for the lecture.

Ivanov typically begins each class by pushing out five questions to students via Learning Catalytics. How well the students answer the questions sets the tone for how he’ll approach the lecture.

“If I notice there’s a question that’s necessary for them to know for the next section and 80 percent of them didn’t get it right, it tells me that maybe I didn’t explain the concept the right way. So I’ll look at an alternative way to explain that concept and hopefully that will be helpful for them to grasp it so they’re ready to learn the new topic.”

The Learning Catalytics exercise normally fills the first 10 minutes of class. Ivanov may also deploy the tool at the end of a class to gauge how well students absorbed the day’s lecture material.

“It doesn’t make sense to move to the next topic if they haven’t completely understood what was covered last class,” says Sasko. “I’ll take my time to go over that concept one more time and maybe use some alternative way. Hopefully that will be more helpful for them.”

Students who miss a class appreciate the Learning Catalytics-powered quizzes because they provide an opportunity to see what they missed and get up to speed.

Guided Lecture Notes from Pearson offer students another valuable tool for organizing and comprehending course content, says Ivanov. He encourages students to use the Notes, along with additional important material from the text, and distill them into one page for use on the final exam.

“I started experimenting with that last year, and the students really liked it,” says Sasko. “I got positive feedback that they were allowed to use those summary notes. Some of them create nice notes.”

Students must upload the notes to their learning management system (LMS), Canvas, providing Ivanov with an opportunity to review and gauge whether they’ll be helpful to the student. He’ll inform students if he doesn’t feel the notes will be helpful, providing them with an opportunity to redo them.

As an added measure, Ivanov creates an extra credit review exam with 40-50 questions to support the Guided Lecture Notes. Students can gauge their performance on the extra credit assignment to help them determine which information to include on the one-page summary they bring to the final exam.

“I hope they go over the notes and extract the most important facts from the section(s) they must remember, or maybe they have a hard time remembering, so they will find it useful on the final exam. If they can’t remember it now, how are they going to remember it on the final exam?”

With the suite of features MyLab Math delivers, Ivanov and his students have a dynamic resource to guide them through challenging curricula with confidence.

Ivanov encourages his peers to adopt MyLab, creating instructional videos to help them navigate and integrate key features.

“I’m really thankful to Pearson,” says Ivanov. “I think it’s a great tool. I see Pearson is constantly updating their platform. They’re doing great things.”

Patrick Golden is a writer, marketing and communications specialist, and former journalist based in Massachusetts.

Like many instructors, I spent years using and teaching with the TI-83 and TI-84 Plus calculators. These devices were considered the standard in classrooms across the country. They were reliable, widely available, and supported by nearly every textbook publisher. For a long time, I had no reason to question whether they were still the best tools for the job.

That changed when my courses transitioned to fully online instruction, and I began using Honorlock to proctor my exams. The issue was not the calculator itself. The real issue was what was hidden from my view when students were using the calculator. During testing, students were often looking down, out of sight of the webcam for long periods of time. I could see their faces but not their hands or their work. From an academic integrity standpoint, this was a major problem. I had no clear way to verify what was happening just below the webcam frame.

As someone who takes academic honesty seriously, I knew I had to make a change. That change came in the form of StatCrunch.

At first, the move to StatCrunch was driven entirely by concerns about exam integrity. Because StatCrunch is accessed directly through the testing screen, students no longer had to look down or shift their focus off screen. It kept their attention on the test and within view of the webcam. This single adjustment immediately improved my ability to monitor exams and reduced the risk of students accessing unauthorized tools or materials.

Exam security was a primary need. To my surprise, I found that students reported higher satisfaction with the platform. They liked that they did not have to memorize sequences of calculator key presses to run a basic statistical test. They appreciated the cleaner interface and the ability to work directly with real data sets. Many students, even those with prior experience using graphing calculators, found StatCrunch to be more intuitive and less intimidating.

Another unexpected benefit was that test completion times dropped significantly. Students were no longer slowed down by the mechanics of navigating multi-step commands on the calculator. They could get results quickly and focus more energy on interpreting those results correctly. That, in turn, allowed me to shift more of my instruction toward critical thinking. Instead of spending large portions of class time explaining how to find a confidence interval using a series of keystrokes, I could focus on what a confidence interval means, how to explain it in plain language, and how to make decisions based on the output.

It also allowed me to stop teaching students how to use a calculator that was never really designed for statistics in the first place. The TI-83 and TI-84 are graphing calculators with a few statistical functions layered on top. Some of the features I needed had to come in the form of downloaded programs, which was a logistical challenge in any classroom medium. StatCrunch, by contrast, was built from the ground up for data analysis.

This experience even prompted me to rethink my approach in other courses, such as College Algebra. Once I saw how much more efficient and transparent things became using modern tools like StatCrunch, I started reevaluating my use of the TI calculators more broadly. That led me to explore Desmos and other platforms that provide powerful visualizations and eliminate the need to teach around the limitations of outdated hardware. What began as a change for one course evolved into a shift in my overall philosophy of technology in math instruction.

In hindsight, I regret not making this switch sooner. What started as a fix for one problem ended up solving many others. It improved the integrity of my exams, boosted student engagement, reduced confusion, and created more space in my course for meaningful learning.

There will always be a place for the TI calculator in some classrooms, especially where testing environments and course goals are different. But for online instruction, especially when paired with remote proctoring, I have no hesitation in saying that StatCrunch has become the right tool for the job.

And I am not going back.

Like his peers at Florida Southern College (FSC) and broadly across higher education, Professor Larry Young is navigating the choppy waters of generative AI in the classroom. Students increasingly turn to tools such as ChatGPT and Gemini to retrieve ready-made answers to difficult questions and concepts in their coursework. But quick wins can shortchange the deeper understanding and critical thinking they need to succeed — now and in the future.

A dynamic eTextbook feature from Pearson becomes a game-changer for non-native English-speaking students at Eastern Florida State College.

Eastern Florida State College (EFSC), with its enrollment of more than 18,000, supports an increasingly diverse student body, including many learners who are native to countries where English is not the primary language.

These students face a dual challenge: becoming proficient in English while navigating the rigors of demanding coursework. The language barrier can be especially acute in science-focused disciplines, such as biology, because layers of opaque terminology can get in the way of comprehension and engagement.

Discouraged, overwhelmed, and often feeling too embarrassed to seek help, these students risk underachieving, and, in some cases, dropping courses enroute to abandoning their academic and professional dreams.

Integrated within its eTexbooks, the Pearson translation tool provides rapid access to accurate, trustworthy translations in more than 130 languages.

At EFSC, this tool reversed the academic trajectories of two struggling non-native English-speaking students who were using Campbell Biology while pursuing careers in healthcare delivery. It also provided an aha moment for their instructor, who had been unaware that a solution to his students’ challenges had been hiding in plain sight.

Dr. Andrew Dutra, associate professor of biology and discipline manager for general biology, biomedical/biotechnology at EFSC used to struggle to support students still honing their English skills.

He knows the challenges collegiate-level biology courses present for his students, and how a lack of English proficiency can render the courses impossible to navigate.

“Biology is its own language,” says Dutra, a New England native who melded his childhood fascination with the living world with his knack for teaching to forge a rewarding career as a higher education instructor. “There’s a lot of technical terminology, especially when it comes to the classification of organisms or biochemical processes.”

On the occasions when Dutra encountered non-native English-speaking students who struggled with English, an effective solution was difficult to find. Widely available tools, such as Google Translate™, delivered hit-or-miss results.

A turning point finally arrived when Dutra sought to support a particular struggling student. A mother of two young children, the student had returned to school to pursue her dream of becoming a nurse. Dutra observed her to be bright, articulate, and diligent. However, her assessments and test scores didn’t reflect the effort she poured into her work. The language barrier proved to be the culprit. A native Arabic speaker, she struggled with the English text, especially the peculiar biology vocabulary.

Dutra first turned to Google to translate his General Biology lab manual into Arabic, but the student reported the translation was more confusing than the regular English text.

Determined to find a solution, Dutra reached out to his Pearson representative, who suggested he try the translation tool available in the eTextbook.

Dutra had been unaware of the feature and quickly introduced it to his student. Together, they selected the English text from the eTextbook and applied the Arabic translation.

“It changed everything,” says Dutra. “Within seconds, the entire page or chapter she was reviewing translated into her language. You could see the relief wash over her. Her shoulders relaxed, and she said, ‘I understand this now.’”

Unlike the unreliable online resources Dutra had tried, Pearson’s translation was accurate and dependable. He asked the student to use the tool to review previously covered material. She soon returned with higher-level questions that reflected how the content had finally clicked with her. She was more engaged and confident moving forward.

“This was a student I feared might not make it through the course,” says Dutra. “She did a complete turnaround and became one of the top performers. This tool was like a godsend for her. She thought she’d have to abandon her nursing dreams, but now she’s well on her way.”

The student continued to find success with the tool, employing it in Anatomy & Physiology I & II, which Dutra teaches. She even proactively mentions the tool to other students.

The wins didn’t stop there. Another one of Dutra’s students, a native Thai speaker who wanted to attend medical school, faced a similar a struggle. Dutra noticed something was amiss when the student needed five or six hours to complete a straightforward multiple-choice quiz. Again, language issues proved to be the culprit.

Dutra reports that the student had resorted to holding her iPhone over the eText on her iPad to snap pictures and translate it into Thai via Google Translate™. The results were disappointing.

This time, Dutra knew exactly what do to.

“When I introduced her to the Pearson translation tool, she almost started weeping,” he recalls. “She told me, ‘I was about to visit my advisor and switch my major to humanities or something else, but now I think I can do it.’”

And do it she has — rapidly becoming one of Dutra’s top performers, just as his Arabic student had.

Dutra now mentions the translation tool to his students at the start of each course.

Its convenience complements its accuracy.

“It’s fully integrated into the courseware,” he explains. “Neither the student nor I must go outside the platform. With a couple of clicks, it translates exactly what they need. Plus, it’s coming from a trusted source, so I don’t have to worry about putting something into Google Translate™, crossing my fingers, and hoping for the best.”