Discrete random variables are characterized by a finite set of values they can take, such as the outcomes of rolling a die. These values can be represented in a table or graph, where the x-axis displays the possible values and the height of the bars indicates their probabilities. Notably, there are gaps between the bars, reflecting that certain values cannot occur simultaneously, such as being greater than one and less than two.

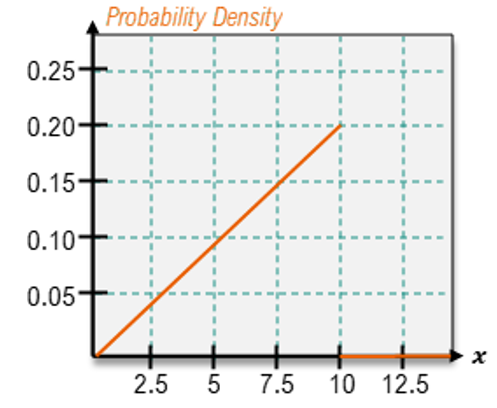

In contrast, continuous random variables can take on any value within a specified range, making them infinitely divisible. For instance, if a continuous random variable x can range from 0 to 6, it can assume any value within that interval, including decimals and irrational numbers like π. This characteristic necessitates the use of a probability density function (PDF) to represent continuous random variables, as listing all possible values in a table is impractical.

To find probabilities for discrete random variables, one can sum the probabilities of the individual values within a specified range. For example, to determine the probability that x is between 1 and 3, one would identify the values 1, 2, and 3, each with a probability of \( \frac{1}{6} \). Adding these gives a total probability of \( \frac{1}{2} \).

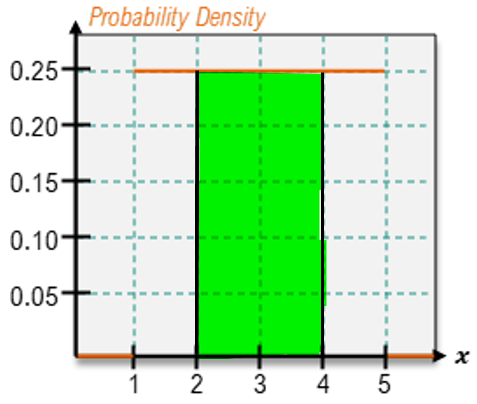

For continuous random variables, however, the approach differs. Since there are infinitely many values between any two points, one cannot simply add probabilities. Instead, the probability is calculated as the area under the PDF over the desired range. For instance, to find the probability that x is between 1 and 3, one would calculate the area of the rectangle formed under the PDF between these two points. If the height of the rectangle is \( \frac{1}{6} \) and the width is 2 (from 1 to 3), the area—and thus the probability—is \( \frac{1}{6} \times 2 = \frac{1}{3} \).

When considering the probability that x equals a specific value, such as 5, the discrete case is straightforward: one simply looks up the assigned probability, which might be \( \frac{1}{6} \). In the continuous case, however, the width of the area at a single point is zero, leading to a probability of zero. This reflects the fact that while 5 is a possible value, the probability of selecting exactly that value among infinitely many options is effectively zero.

Lastly, the uniform distribution is a specific type of continuous distribution where the probability density is constant across all values of x. This means that the height of the PDF remains the same for every possible value, indicating equal likelihood for all outcomes within the defined range. Not all continuous random variables exhibit a uniform distribution; it is essential to analyze the PDF to determine its characteristics.

Understanding these distinctions between discrete and continuous random variables, as well as the methods for calculating their probabilities, is crucial for effectively working with statistical data and probability theory.

;

;  ;

;  ;

;  ;

;

;

;  ;

;  ;

;