Table of contents

- 1. Introduction to Accounting1h 21m

- 2. Transaction Analysis1h 13m

- 3. Accrual Accounting Concepts2h 38m

- Accrual Accounting vs. Cash Basis Accounting10m

- Revenue Recognition and Expense Recognition24m

- Introduction to Adjusting Journal Entries and Prepaid Expenses36m

- Adjusting Entries: Supplies12m

- Adjusting Entries: Unearned Revenue11m

- Adjusting Entries: Accrued Expenses12m

- Adjusting Entries: Accrued Revenues6m

- Adjusting Entries: Depreciation16m

- Summary of Adjusting Entries7m

- Unadjusted vs Adjusted Trial Balance6m

- Closing Entries10m

- Post-Closing Trial Balance2m

- 4. Merchandising Operations2h 30m

- Service Company vs. Merchandising Company10m

- Net Sales28m

- Cost of Goods Sold - Perpetual Inventory vs. Periodic Inventory9m

- Perpetual Inventory - Purchases10m

- Perpetual Inventory - Freight Costs9m

- Perpetual Inventory - Purchase Discounts11m

- Perpetual Inventory - Purchasing Summary6m

- Periodic Inventory - Purchases14m

- Periodic Inventory - Freight Costs7m

- Periodic Inventory - Purchase Discounts10m

- Periodic Inventory - Purchasing Summary6m

- Single-step Income Statement4m

- Multi-step Income Statement17m

- Comprehensive Income2m

- 5. Inventory1h 55m

- Merchandising Company vs. Manufacturing Company6m

- Physical Inventory Count, Ownership of Goods, and Consigned Goods10m

- Specific Identification7m

- Periodic Inventory - FIFO, LIFO, and Average Cost23m

- Perpetual Inventory - FIFO, LIFO, and Average Cost31m

- Financial Statement Effects of Inventory Costing Methods10m

- Lower of Cost or Market11m

- Inventory Errors14m

- 6. Internal Controls and Reporting Cash1h 16m

- 7. Receivables and Investments3h 8m

- Types of Receivables8m

- Net Accounts Receivable: Direct Write-off Method5m

- Net Accounts Receivable: Allowance for Doubtful Accounts13m

- Net Accounts Receivable: Percentage of Sales Method9m

- Net Accounts Receivable: Aging of Receivables Method11m

- Notes Receivable25m

- Introduction to Investments in Securities13m

- Trading Securities31m

- Available-for-Sale (AFS) Securities26m

- Held-to-Maturity (HTM) Securities17m

- Equity Method25m

- 8. Long Lived Assets5h 2m

- Initial Cost of Long Lived Assets42m

- Basket (Lump-sum) Purchases13m

- Ordinary Repairs vs. Capital Improvements10m

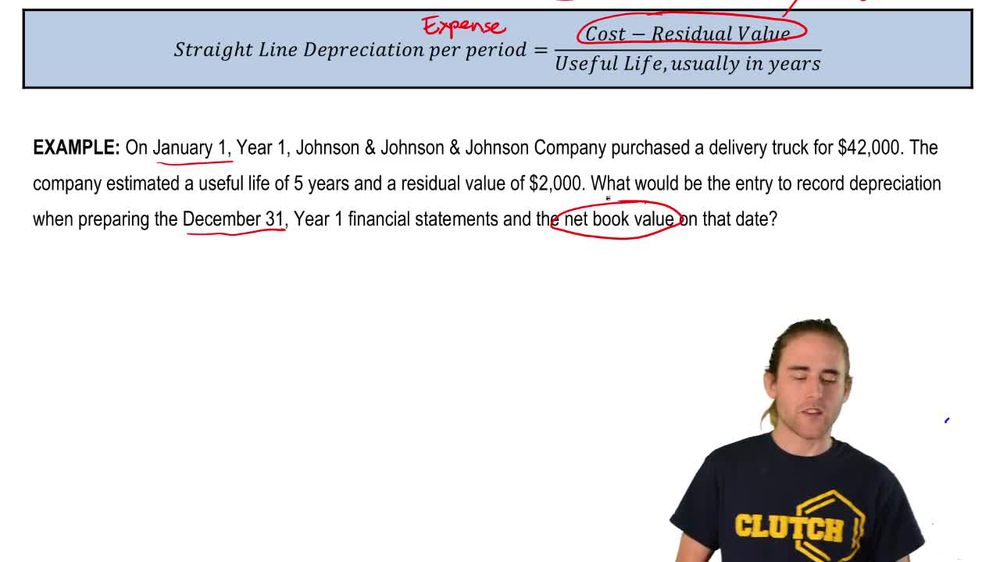

- Depreciation: Straight Line32m

- Depreciation: Declining Balance29m

- Depreciation: Units-of-Activity28m

- Depreciation: Summary of Main Methods8m

- Depreciation for Partial Years13m

- Retirement of Plant Assets (No Proceeds)14m

- Sale of Plant Assets18m

- Change in Estimate: Depreciation21m

- Intangible Assets and Amortization17m

- Natural Resources and Depletion16m

- Asset Impairments16m

- Exchange for Similar Assets16m

- 9. Current Liabilities2h 19m

- 10. Time Value of Money1h 23m

- 11. Long Term Liabilities2h 45m

- 12. Stockholders' Equity2h 15m

- Characteristics of a Corporation17m

- Shares Authorized, Issued, and Outstanding9m

- Issuing Par Value Stock12m

- Issuing No Par Value Stock5m

- Issuing Common Stock for Assets or Services8m

- Retained Earnings14m

- Retained Earnings: Prior Period Adjustments9m

- Preferred Stock11m

- Treasury Stock9m

- Dividends and Dividend Preferences17m

- Stock Dividends10m

- Stock Splits9m

- 13. Statement of Cash Flows2h 24m

- 14. Financial Statement Analysis5h 25m

- Horizontal Analysis14m

- Vertical Analysis23m

- Common-sized Statements5m

- Trend Percentages7m

- Discontinued Operations and Extraordinary Items6m

- Introduction to Ratios8m

- Ratios: Earnings Per Share (EPS)10m

- Ratios: Working Capital and the Current Ratio14m

- Ratios: Quick (Acid Test) Ratio12m

- Ratios: Gross Profit Rate9m

- Ratios: Profit Margin7m

- Ratios: Quality of Earnings Ratio8m

- Ratios: Inventory Turnover10m

- Ratios: Average Days in Inventory9m

- Ratios: Accounts Receivable (AR) Turnover9m

- Ratios: Average Collection Period (Days Sales Outstanding)8m

- Ratios: Return on Assets (ROA)8m

- Ratios: Total Asset Turnover5m

- Ratios: Fixed Asset Turnover5m

- Ratios: Profit Margin x Asset Turnover = Return On Assets9m

- Ratios: Accounts Payable Turnover6m

- Ratios: Days Payable Outstanding (DPO)8m

- Ratios: Times Interest Earned (TIE)7m

- Ratios: Debt to Asset Ratio5m

- Ratios: Debt to Equity Ratio5m

- Ratios: Payout Ratio5m

- Ratios: Dividend Yield Ratio7m

- Ratios: Return on Equity (ROE)10m

- Ratios: DuPont Model for Return on Equity (ROE)20m

- Ratios: Free Cash Flow10m

- Ratios: Price-Earnings Ratio (PE Ratio)7m

- Ratios: Book Value per Share of Common Stock7m

- Ratios: Cash to Monthly Cash Expenses8m

- Ratios: Cash Return on Assets7m

- Ratios: Economic Return from Investing6m

- Ratios: Capital Acquisition Ratio6m

- 15. GAAP vs IFRS56m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Introduction7m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Classified Balance Sheet6m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Recording Differences4m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Adjusting Entries4m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Merchandising3m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Inventory3m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Fraud, Internal Controls, and Cash3m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Receivables2m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Long Lived Assets5m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Liabilities3m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Stockholders' Equity3m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Statement of Cash Flows5m

- GAAP vs. IFRS: Analysis and Income Statement Presentation5m

8. Long Lived Assets

Depreciation: Straight Line

Struggling with Financial Accounting?

Join thousands of students who trust us to help them ace their exams!Watch the first video

Introduction to Depreciation

Brian Krogol

Video duration:

11mPlay a video: