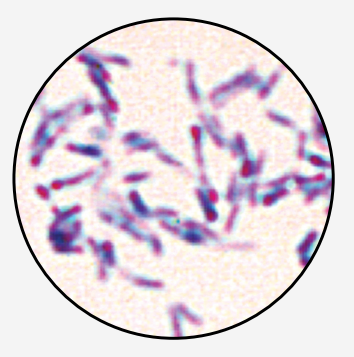

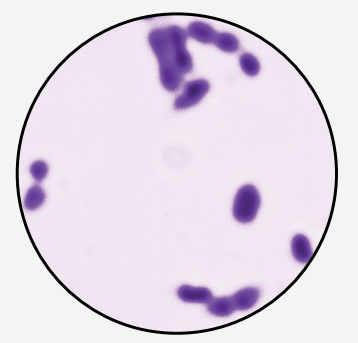

Diphtheria is a serious upper respiratory tract infection caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae, which is a gram-positive, non-endospore-forming rod-shaped bacterium often described as club-shaped due to its thicker ends. The pathogenicity of C. diphtheriae arises from an exotoxin it produces, but only when the bacterium is lysogenized by a bacteriophage—a virus that infects bacteria. This phage carries the gene encoding the exotoxin, meaning the bacteria alone are not harmful unless infected by the phage.

The exotoxin is a potent protein composed of two parts: one facilitates entry into host cells, and the other enzymatically inhibits protein synthesis by inactivating elongation factor-2 (EF-2). This inhibition leads to cell death and can cause severe complications such as heart, kidney, and nerve damage, potentially resulting in fatality. While C. diphtheriae can also cause skin infections, these are less dangerous because the exotoxin is poorly absorbed through the skin.

Diphtheria spreads primarily through respiratory droplets during close contact, but transmission can also occur via contact with contaminated objects. The hallmark symptom is the formation of a pseudomembrane in the throat, a thick layer of fibrin and dead cells that can obstruct the airway and cause suffocation. This pseudomembrane adheres tightly to the underlying tissue, making removal difficult and potentially harmful. Other symptoms include a sore throat, fever, weakness, and a characteristic swollen neck known as "bull neck."

Diagnosis involves confirming the presence of C. diphtheriae and its exotoxin. This is achieved through bacterial culture on selective and differential media, immunoassays such as the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to detect the exotoxin, and molecular techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to identify the toxin gene.

Treatment combines antibiotics, such as erythromycin or penicillin, to eliminate the bacteria, with administration of diphtheria antitoxin to neutralize circulating exotoxin. The antitoxin is crucial because the toxin irreversibly inhibits protein synthesis within host cells, and antibiotics alone cannot reverse this damage.

Prevention is effectively managed through vaccination with the DTaP vaccine, which includes a diphtheria toxoid component. This toxoid vaccine stimulates immunity against the exotoxin rather than the bacteria itself, providing protection against the most dangerous effects of the disease. Booster vaccines such as Tdap and Td maintain immunity in older children and adults, differing slightly in formulation but continuing to protect against diphtheria and tetanus.