Table of contents

- 1. Intro to General Chemistry3h 48m

- Classification of Matter18m

- Physical & Chemical Changes19m

- Chemical Properties7m

- Physical Properties5m

- Intensive vs. Extensive Properties13m

- Temperature12m

- Scientific Notation13m

- SI Units7m

- Metric Prefixes24m

- Significant Figures9m

- Significant Figures: Precision in Measurements8m

- Significant Figures: In Calculations14m

- Conversion Factors16m

- Dimensional Analysis17m

- Density12m

- Density of Geometric Objects19m

- Density of Non-Geometric Objects7m

- 2. Atoms & Elements4h 16m

- The Atom9m

- Subatomic Particles15m

- Isotopes17m

- Ions27m

- Atomic Mass28m

- Periodic Table: Classifications11m

- Periodic Table: Group Names8m

- Periodic Table: Representative Elements & Transition Metals7m

- Periodic Table: Element Symbols6m

- Periodic Table: Elemental Forms6m

- Periodic Table: Phases8m

- Periodic Table: Charges20m

- Calculating Molar Mass10m

- Mole Concept30m

- Law of Conservation of Mass5m

- Law of Definite Proportions10m

- Atomic Theory9m

- Law of Multiple Proportions3m

- Millikan Oil Drop Experiment7m

- Rutherford Gold Foil Experiment10m

- 3. Chemical Reactions4h 10m

- Empirical Formula18m

- Molecular Formula20m

- Combustion Analysis38m

- Combustion Apparatus15m

- Polyatomic Ions24m

- Naming Ionic Compounds11m

- Writing Ionic Compounds7m

- Naming Ionic Hydrates6m

- Naming Acids18m

- Naming Molecular Compounds6m

- Balancing Chemical Equations13m

- Stoichiometry16m

- Limiting Reagent17m

- Percent Yield19m

- Mass Percent4m

- Functional Groups in Chemistry11m

- 4. BONUS: Lab Techniques and Procedures1h 36m

- 5. BONUS: Mathematical Operations and Functions48m

- 6. Chemical Quantities & Aqueous Reactions3h 53m

- Solutions6m

- Molarity18m

- Osmolarity15m

- Dilutions15m

- Solubility Rules15m

- Electrolytes18m

- Molecular Equations18m

- Gas Evolution Equations13m

- Solution Stoichiometry14m

- Complete Ionic Equations18m

- Calculate Oxidation Numbers15m

- Redox Reactions17m

- Balancing Redox Reactions: Acidic Solutions17m

- Balancing Redox Reactions: Basic Solutions17m

- Activity Series10m

- 7. Gases3h 50m

- Pressure Units6m

- The Ideal Gas Law18m

- The Ideal Gas Law Derivations13m

- The Ideal Gas Law Applications6m

- Chemistry Gas Laws13m

- Chemistry Gas Laws: Combined Gas Law12m

- Mole Fraction of Gases6m

- Partial Pressure19m

- The Ideal Gas Law: Molar Mass13m

- The Ideal Gas Law: Density14m

- Gas Stoichiometry18m

- Standard Temperature and Pressure14m

- Effusion14m

- Root Mean Square Speed9m

- Kinetic Energy of Gases10m

- Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution8m

- Velocity Distributions4m

- Kinetic Molecular Theory14m

- Van der Waals Equation9m

- 8. Thermochemistry2h 37m

- Nature of Energy6m

- Kinetic & Potential Energy7m

- First Law of Thermodynamics7m

- Internal Energy8m

- Endothermic & Exothermic Reactions7m

- Heat Capacity19m

- Constant-Pressure Calorimetry24m

- Constant-Volume Calorimetry10m

- Thermal Equilibrium8m

- Thermochemical Equations12m

- Formation Equations9m

- Enthalpy of Formation12m

- Hess's Law23m

- 9. Quantum Mechanics2h 58m

- Wavelength and Frequency6m

- Speed of Light8m

- The Energy of Light13m

- Electromagnetic Spectrum10m

- Photoelectric Effect17m

- De Broglie Wavelength9m

- Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle17m

- Bohr Model14m

- Emission Spectrum5m

- Bohr Equation13m

- Introduction to Quantum Mechanics5m

- Quantum Numbers: Principal Quantum Number5m

- Quantum Numbers: Angular Momentum Quantum Number10m

- Quantum Numbers: Magnetic Quantum Number11m

- Quantum Numbers: Spin Quantum Number9m

- Quantum Numbers: Number of Electrons11m

- Quantum Numbers: Nodes6m

- 10. Periodic Properties of the Elements3h 9m

- The Electron Configuration22m

- The Electron Configuration: Condensed4m

- The Electron Configurations: Exceptions13m

- The Electron Configuration: Ions12m

- Paramagnetism and Diamagnetism8m

- The Electron Configuration: Quantum Numbers16m

- Valence Electrons of Elements12m

- Periodic Trend: Metallic Character3m

- Periodic Trend: Atomic Radius8m

- Periodic Trend: Ionic Radius13m

- Periodic Trend: Ionization Energy12m

- Periodic Trend: Successive Ionization Energies11m

- Periodic Trend: Electron Affinity10m

- Periodic Trend: Electronegativity5m

- Periodic Trend: Effective Nuclear Charge21m

- Periodic Trend: Cumulative12m

- 11. Bonding & Molecular Structure3h 29m

- Lewis Dot Symbols10m

- Chemical Bonds13m

- Dipole Moment11m

- Octet Rule10m

- Formal Charge9m

- Lewis Dot Structures: Neutral Compounds20m

- Lewis Dot Structures: Sigma & Pi Bonds14m

- Lewis Dot Structures: Ions15m

- Lewis Dot Structures: Exceptions14m

- Lewis Dot Structures: Acids15m

- Resonance Structures21m

- Average Bond Order4m

- Bond Energy15m

- Coulomb's Law6m

- Lattice Energy12m

- Born Haber Cycle14m

- 12. Molecular Shapes & Valence Bond Theory1h 58m

- 13. Liquids, Solids & Intermolecular Forces2h 23m

- Molecular Polarity10m

- Intermolecular Forces20m

- Intermolecular Forces and Physical Properties11m

- Clausius-Clapeyron Equation18m

- Phase Diagrams13m

- Heating and Cooling Curves27m

- Atomic, Ionic, and Molecular Solids11m

- Crystalline Solids4m

- Simple Cubic Unit Cell7m

- Body Centered Cubic Unit Cell12m

- Face Centered Cubic Unit Cell6m

- 14. Solutions3h 1m

- Solutions: Solubility and Intermolecular Forces17m

- Molality15m

- Parts per Million (ppm)13m

- Mole Fraction of Solutions8m

- Solutions: Mass Percent12m

- Types of Aqueous Solutions8m

- Intro to Henry's Law4m

- Henry's Law Calculations12m

- The Colligative Properties14m

- Boiling Point Elevation16m

- Freezing Point Depression10m

- Osmosis19m

- Osmotic Pressure10m

- Vapor Pressure Lowering (Raoult's Law)16m

- 15. Chemical Kinetics2h 53m

- 16. Chemical Equilibrium2h 29m

- 17. Acid and Base Equilibrium5h 2m

- Acids Introduction9m

- Bases Introduction7m

- Binary Acids15m

- Oxyacids10m

- Bases14m

- Amphoteric Species5m

- Arrhenius Acids and Bases5m

- Bronsted-Lowry Acids and Bases21m

- Lewis Acids and Bases12m

- The pH Scale16m

- Auto-Ionization9m

- Ka and Kb16m

- pH of Strong Acids and Bases9m

- Ionic Salts17m

- pH of Weak Acids31m

- pH of Weak Bases32m

- Diprotic Acids and Bases8m

- Diprotic Acids and Bases Calculations30m

- Triprotic Acids and Bases9m

- Triprotic Acids and Bases Calculations17m

- 18. Aqueous Equilibrium4h 47m

- Intro to Buffers20m

- Henderson-Hasselbalch Equation19m

- Intro to Acid-Base Titration Curves13m

- Strong Titrate-Strong Titrant Curves9m

- Weak Titrate-Strong Titrant Curves15m

- Acid-Base Indicators8m

- Titrations: Weak Acid-Strong Base38m

- Titrations: Weak Base-Strong Acid41m

- Titrations: Strong Acid-Strong Base11m

- Titrations: Diprotic & Polyprotic Buffers32m

- Solubility Product Constant: Ksp17m

- Ksp: Common Ion Effect18m

- Precipitation: Ksp vs Q12m

- Selective Precipitation9m

- Complex Ions: Formation Constant18m

- 19. Chemical Thermodynamics1h 50m

- 20. Electrochemistry2h 42m

- 21. Nuclear Chemistry2h 37m

- Intro to Radioactivity10m

- Alpha Decay9m

- Beta Decay7m

- Gamma Emission7m

- Electron Capture & Positron Emission9m

- Neutron to Proton Ratio7m

- Band of Stability: Alpha Decay & Nuclear Fission10m

- Band of Stability: Beta Decay3m

- Band of Stability: Electron Capture & Positron Emission4m

- Band of Stability: Overview14m

- Measuring Radioactivity7m

- Rate of Radioactive Decay12m

- Radioactive Half-Life16m

- Mass Defect19m

- Nuclear Binding Energy14m

- 22. Organic Chemistry5h 7m

- Introduction to Organic Chemistry8m

- Structural Formula8m

- Condensed Formula10m

- Skeletal Formula6m

- Spatial Orientation of Bonds3m

- Intro to Hydrocarbons16m

- Isomers11m

- Chirality15m

- Functional Groups in Chemistry11m

- Naming Alkanes4m

- The Alkyl Groups9m

- Naming Alkanes with Substituents13m

- Naming Cyclic Alkanes6m

- Naming Other Substituents8m

- Naming Alcohols11m

- Naming Alkenes11m

- Naming Alkynes9m

- Naming Ketones5m

- Naming Aldehydes5m

- Naming Carboxylic Acids4m

- Naming Esters8m

- Naming Ethers5m

- Naming Amines5m

- Naming Benzene7m

- Alkane Reactions7m

- Intro to Addition Reactions4m

- Halogenation Reactions4m

- Hydrogenation Reactions3m

- Hydrohalogenation Reactions7m

- Alcohol Reactions: Substitution Reactions4m

- Alcohol Reactions: Dehydration Reactions9m

- Intro to Redox Reactions8m

- Alcohol Reactions: Oxidation Reactions7m

- Aldehydes and Ketones Reactions6m

- Ester Reactions: Esterification4m

- Ester Reactions: Saponification3m

- Carboxylic Acid Reactions4m

- Amine Reactions3m

- Amide Formation4m

- Benzene Reactions10m

- 23. Chemistry of the Nonmetals2h 39m

- Main Group Elements: Bonding Types4m

- Main Group Elements: Boiling & Melting Points7m

- Main Group Elements: Density11m

- Main Group Elements: Periodic Trends7m

- The Electron Configuration Review16m

- Periodic Table Charges Review20m

- Hydrogen Isotopes4m

- Hydrogen Compounds11m

- Production of Hydrogen8m

- Group 1A and 2A Reactions7m

- Boron Family Reactions7m

- Boron Family: Borane7m

- Borane Reactions7m

- Nitrogen Family Reactions12m

- Oxides, Peroxides, and Superoxides12m

- Oxide Reactions4m

- Peroxide and Superoxide Reactions6m

- Noble Gas Compounds3m

- 24. Transition Metals and Coordination Compounds3h 16m

- Atomic Radius & Density of Transition Metals11m

- Electron Configurations of Transition Metals7m

- Electron Configurations of Transition Metals: Exceptions11m

- Paramagnetism and Diamagnetism10m

- Ligands10m

- Complex Ions5m

- Coordination Complexes7m

- Classification of Ligands11m

- Coordination Numbers & Geometry9m

- Naming Coordination Compounds22m

- Writing Formulas of Coordination Compounds8m

- Isomerism in Coordination Complexes15m

- Orientations of D Orbitals4m

- Intro to Crystal Field Theory10m

- Crystal Field Theory: Octahedral Complexes5m

- Crystal Field Theory: Tetrahedral Complexes4m

- Crystal Field Theory: Square Planar Complexes4m

- Crystal Field Theory Summary8m

- Magnetic Properties of Complex Ions9m

- Strong-Field vs Weak-Field Ligands6m

- Magnetic Properties of Complex Ions: Octahedral Complexes11m

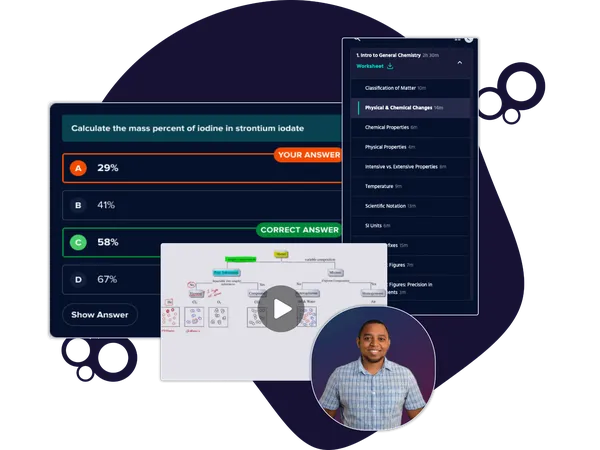

10. Periodic Properties of the Elements

The Electron Configuration

Electron Configurations

Pearson

Video duration:

1mPlay a video:

Related Videos

Related Practice